Status: Under development, and needs revision

Last edit: December 6, 2018

Why people do good –– cowardice as the source of good behaviour –– attraction to jerks –– how to make people be good –– crime enforcement –– what is goodness –– selfishness and altrusim –– Cooperativity as an alternative to altruism –– Cooperation with whom?

Why people do good

Goodness out of Cowardice

The Stanford Prison Experiment

I had been reading Zimbardo’s “The Lucifer Effect”, which details his “Stanford Prison Experiment”. In the experiment a group of volunteers, mostly but not exclusively Stanford students, were randomly assigned to two groups, one of “prisoners” and the other of “prison guards”. An unused basement somewhere on campus was converted to a makeshift prison where the prisoners were to remain for a duration of two weeks, watched over 24 hours by guards who did their duty in three 8 hours shifts.

While I find the experiment to be important and the book with its detailed day-to-day description of events to be an important account of it, I also found the book very upsetting to read, and mostly due to what I perceived to be Zimbardo’s amateurish job of running the experiment. It is clear from his writing that he became aware after the fact of how he succumbed into his own make-believe fiction (for the duration of the experiment he assumed the role of “superintendent”) instead of being a detached outside observer, and how he should have done things differently. But I also got the impression that some things still eluded him and that he hadn’t quite learned his lesson.

To give one example, there were several prisoners that were released from the experiment before its complete secession (which also occurred earlier than had been planned). The first one, Doug Korpi, was released after showing extreme signs of distress. It had been a dilemma for Zimbardo whether Korpi’s behaviour was “real”/ authentic, or whether he was simply “acting out” in order to be let of the experiment. He admitted that after the decision to release him, which was debated for a long time between him and his colleagues who assumed prison ward duties, had been made, it seemed retrospectively obvious that that was the right decision.1 However, there is no indication in the book that Zimbardo saw the irony in his original question. The whole experiment, after all, is a big “acting out”.2 While he conceded to the fact that an experimentee’s wellbeing was more important than the experiment itself, he failed to see that the distinction between his subjects as experimentees and his subjects as prisoners or guards (a duplicity he had also put himself into) was impossible to distangle, even though the experiment in the first place was meant to investigate how assigned roles (identities imposed from without) affected the behaviours of the people they were assigned to (the “real” identities)3.

It could be claimed that his concern about whether Korpi was “faking it” or not was beside Zimbardo’s being taken up by the illusion he had created, and that it was a concern about a contract made “in the real world”. Namely, the experimentees signed a form4 in which they consented to participate in the experiment. Running the experiment was Zimbardo’s interest, and so the experimentee’s were rendering him a service; for that service he was remunerating them. Obviously it will do Zimbardo no good if all subjects quit on the first day. At the same time, remuneration was specified in dollars per day,5 a payment that was an important motivation for many of the volunteers, suggesting that a premature termination is within the contract. This is made explicit on the experiment description5 in the line, “Failure to fulfill this contract will result in a partial loss of salary accumulated – according to a prearranged schedule to be agreed upon.” In all cases where prisoners wanted to leave the experiment Zimbardo made the “noble” gesture of offering them the payment for the full duration of two weeks even if they leave ––– for “legitimate reasons” ––– the experiment prematurely. While forthcoming, this very gesture entrapped Zimbardo, making him scrutinize those prisoners and doubt, as it were, their reasons to leave prematurely ––– do they “really” have to stop participating, or do they only pretend to? At the end Zimbardo was no less a subject of his own experiment than the volunteers he signed on the task.

A striking example of that is where Zimbardo retrospectively realized that it was a crazy delusion that he had been into when he was preparing with Sun Tzuish tactics for the event portended by rumours, namely, that the released Korpi was going to return with some friends to trash the prison and the experiment. He mentioned several times in the book the idea he had had at that opportunity to “re-imprison” Korpi, who had clearly been released on “false pretense”. To me that was an absolutely maniacal idea. I got a sense from Zimbardo the author that what he perceived to be delusional was his heeding the rumour, as opposed to his reaction to it (“let’s reimprison Doug”) which in my view is the real bonkers part. That is, that he had felt like he had the legitimate authority to imprison(!) anybody. Zimbardo felt like he was really part of a legal enforcement institution. A sober person with firm conviction that he or his belonging are about to be assaulted would have contacted the police. By the way, the “heeding the rumours” part by itself was not so delusional, not directly, though a little short-sighted. It is not so clear whether Korpi had ever had real plans to do that, namely return with friends and ruin the experimental settings, but I imagine that it is very likely that he did imagine himself doing so, and that his talking about it to other prisoners was what led to the rumours. However, I also think that once he was out of this prison he was also “out of the game”, the whole experience circumscribed, and the vindictive plans left behind with the game, just like announcements of intentions to eradicate a rival player and his progeny off the face of the earth are left behind once the game of Risk is over, and bare no effect whatsoever on the relationship between the two players thenceforth. But, of course, while Korpi left the game, Zimbardo remained inside of it, which means that for the latter the former was still in the same game, and so the threat was, in a sense, real. In other words, the threat was part of the game, it remained after Korpi’s leaving since he and Zimbardo didn’t have an interaction “out of character”, and Zimbardo’s reality was still that game.

I didn’t read the book in its entirety; the shift-to-shift narration proved to be too detailed to me, perhaps, but mostly I kept on being agitated by Zimbardo’s actions. I might have been too quick to judge and to abandon my trust in his analysis, but I found Zimbardo’s model of “situational forces/causes” to lack power of explanation. It is merely descriptive, and merely of the very surface. I think that by drawing the distinction between “dispositional” and “situational causes” he failed to see that it is not “either or” but rather, like the relationship between form and content, the “situational” is being dynamically formed by the constitutional “dispositional”. However, the book did turn to be a source of edification, albeit indirectly. First, its recounting of the Rwandan Genocide and other such horrors informed me about how the slaughtering and raping took place on the interpersonal level. To me it seemed like an unbelievable horror. But then I suddenly saw what was going on, I thought, both there and in the much milder prison experiment. And this sudden insight came not from Zimbardo himself, and not even from his book. The source was one of the experiment subjects, Dave Eschleman, who was cast as a prison guard and who acted as one of their cruelest. At the end of a half-hour BBC documentary we hear him speak at a debriefing where Zimbardo and the participants sat down together two months later to discuss what had transpired in the experiment. Addressing one of the experimentees who had been cast as a prisoner and now sat next to him, he talked about his cruel actions:

I was running little experiments of my own. I wanted to see just what kind of verbal abuse that [sic] people can take before they start objecting, before they start lashing back, under the circumstances.

And he continued:

It surprised me that no one said anything to stop me, they just accepted what I said. And no one questioned my authority at all. And it really shocked me. Why didn’t people… when I started to get… abuse people… I started to get so profane that… and still people didn’t say anything.6

And this is where I had my eureka moment.

Four criticisms of Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect

There were a few guards who hated to see the prison suffer. They never did anything which would be demeaning of the prisoners. The interesting thing is, none of the good guards ever intervened in the behaviour of the guards who gradually became more and more sadistic over time. We’d like to think that there is this core of human nature, that good people can’t do bad things and that good people will dominate over bad situations. In fact, one way to look at the Stanford prison study is that, we put good people in an evil place and we saw who won, well, the sad message is, in this case, the evil place won over the good people.7

Unfortunately, the interesting thing remains interesting at the conclusion of this study, as Zimbardo provides no sufficient explanation for this phenomenon. Worse, however, is that his text is full misguided and rather ambiguous interpretation, stemming from a conceptual framework that is not at all adequate for elucidating the subject matter.

The eleventh and twelfth chapters seem to be the most analytical, “generalising”, of the book. The eleventh consists mostly of different examples taken from “scientific” experiments, non-scientific “experiments” and from “real world phenomena” such as the shocking “strip search phone call scam”8, which evoke people’s conformity with authority figures. The twelfth discusses deindividuation (anonymization of perpetrators, their shedding off of responsibility), dehumanization (the degradation of the victims) and the passive bystanding of indignated spectators.

I think many of the phenomena and concepts Zimbardo presented are not false, but I think he was not thorough and serious enough at investigating what underlies them, was too fixated on his notion of “situational” which was often applied in a nebulous way, and failed to apply the general on the particular, thus misjudging it.

While ostensibly acknowledging the complexity of social situations, Zimbardo repeatedly evoked the notions of “good” and “evil” in a matter that I think should not exit the bounds of fairy tales. In the very beginning of the book (p.6) he warns us from dichotomous good/evil thinking, but later he himself applied it, only shifting the objects onto which he projected these notions. Good and evil were attributed not just to people, but also ––– and somewhat vaguely ––– to situations (as well as “places”, which were used rather interchangeably by Zimbardo). More specifically, situations and places can be “evil”, while people are “good” until they enter such a situation. On that same line of thought, heroism stems from one’s abilities to resist the “influence of situational forces” (p. 486), i.e. the power of the “evil place”. There are several problems with this.

Good people and evil places

First, while he stated that the “situational analysis” of “evil acts” did not condone or acquit them, it is hard not to read this book as claiming that all evil actions ––– with the exception, perhaps, of severe cases of people that are both out of touch with reality and violent by inclination ––– stem solely from the “situation”. The more so given Zimbardo’s treatment of his own experiment (more on this below) and for the fact that he had served as an “expert witness” –– promulgating, of course, his “the situation is evil” dictum –– on cases such as the Abu Ghrib’s abuses.

As Zimbardo didn’t define what a “situation” or “place” was, a person trying to generalize from the book might take “situation” to simply stand for “context” so that it is not restricted in time and place like a Greek play but could stand for the entire life experience of a person,

making any

perpetration the result of “external evil influences”, an evil situation that might be indeed all that a person had known in his lifetime.

The word “place” might suggest otherwise, but Zimbardo does treat Nazi Germany inclusively, a “situation” that lasted more than a decade and across many squared kilometers.

The issue is that given a deterministic world, one can always find a causal chain of events that led to any event or human behaviour, but this really should not effect the judgment of the behaviour itself. An act is not “more bad” because you do not know the story behind it, and, conversely, not “less bad” because you do.

And then this prevailing notion in the book that all people are good is contrary to the experience of each and every person that some people, extreme cases of violence aside, are “more good” or “less good” than others; some are more honest and some are dishonest; some can hold their composure better while others are more irascible; some are more attentive, some are more giving, and so on. Moreover, everyone judges others not merely by what they have already done, but also by how that suggests they might act and behave in some future potential scenario which is less day-to-day; that’s in essence what trust is.

While circumstances exert a strong influence of how people behave ––– or what else? we do not float in a bubbly vat ––– different people would behave differently in those same circumstances.

Zimbardo’s downplaying people’s personality to nothing in favour of “situational factors” is very much akin to B. F. Skinner’s radical behaviourism that negated the influence of genes on the acquisition of behaviour.9 In a sense, “being good” in Zimbardo’s book stops being an attribute of a person as a person, one that distinguishes her from some others, but an indicator of where they stand within Zimbardo’s (almost biblical) scheme that stretches out roughly so:

Good person > Entrance into a Bad Situation > Conformation > Evil Deeds.

Good vs. Ordinary

Second, “good” and “ordinary” ––– as a descriptive modifier of “people” ––– is applied rather interchangeably throughout the book.10

It seems apropos to direct the attention to the derivation of the word “ordinary” from “order”, though this etymological relation, even if informative, is incidental to the main point to be made; we could also use “normal” but assume that our object is a member of civil society, i.e. not a society in an anomic situation, and in which, therefore, the great majority of people conform to a social order.

These two words refer to distinct facets of a person. To put it simplistically, while being “good”, be it a person or an act, is a trait pertaining to a moral-ethical standard, “ordinary”, or, indeed, “orderly”, refers to a degree of conformity. That is, how “ordinary” a person is indicates how similar is his behaviour to that of fellow people in society.

By conflating the two an important point is being missed, and Zimbardo missed it because he failed entirely to consider the function of order and conformity (discussed below).

He certainly didn’t fail to see that conformity with “bad norms” leads to “bad behaviour”,11 but here too, as above, this phenomenon was restricted to its part of a rigid scheme, and what lies underneath it was not properly answered.

For example, while stating previous experiments such at the Milgram experiment he mentions how the rate of conformation to the authority that issues the command to electrocute another human being could be manipulated by varying different experimental conditions, such that in a particular setup conformation would be very low and in another very high, but he doesn’t address the question of what factor it was that led to the variance in the outcome, namely, the rate at which experimentees conformed; what was it in the 10% of the trials that made the experimentees behave differently than the other 90%? One option is that it was something about the way the experiment was ran from the experimenter’s side; since part of the experiment involves an actor, the confederate of the experimenter, that interacts with the experimentee in the role of the authority, it is possible that a variation of his performance, the strict script he was following notwithstanding, brought out different behaviour in the experimentee. Another option ––– which I find more likely, or more significant –– is that it was something in the experimentees themselves that led to their different behaviour. What could it be? Their mood? Their absolute height? Their height relatively to that of the authority? Their character? What they had for breakfast?

That it’s probably the state or attributes of the person that leads to the variance in outcome is suggested by another similar experiment where at the analysis a rough split based on the characteristics of the experimentees was made.12 The experiment was very similar to that of Milgram, only now the electrocuted was a puppy and not a human being, the shocks were actual as opposed to simulated, and the experimentees witnessed the electrocuted directly as opposed to only having him being heard through an intercom system. The split in analysis was between male and female subjects, and it found that 54% (7/13) of males and 100% (13/13) of the female subjects complied completely and electrocuted the puppy using the maximum available shock strength. Since the experimentees weren’t involved in a sexual relation with neither the electrocuted nor with the authority figure, it seems like something else than the subjects’ sex per se that led to the significantly differences in response. It could be a physiological difference, such as in hormonal makeup.13 Another option is that it was a gender-based difference in upbringing and life experience which, for example, led to a variance in the degree of submission to the authority14 in the experiment, or in the “available” coping mechanisms.15 16

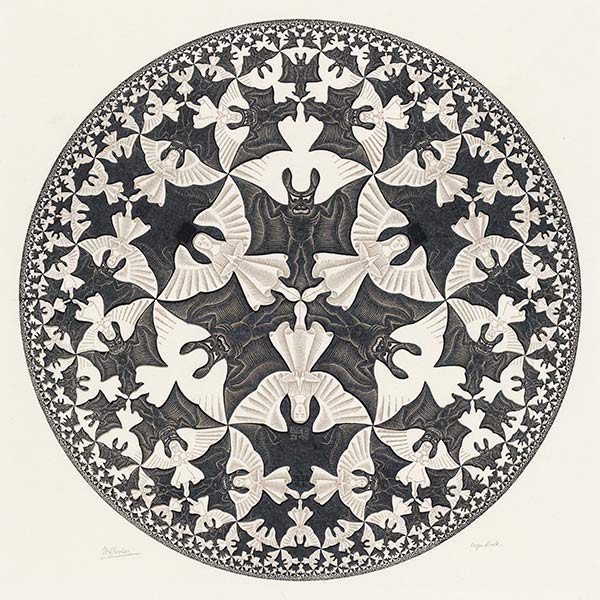

Zimbardo asks the question how “ordinary people” might perpetrate evil acts, but it seems obvious to me that here the perpetration is not “despite” but precisely “because” of their ordinariness, their ordliness. In his preface Zimbardo write that “the rebels [against evil norms] can be considered heroes”, seeming to acklowledge that defiance, that is, non-ordliness, is a component of the heroic, but he contiuous writing that while “we” come to think about heroes as special, they are not so at all. Indeed, in the last chapter of the book, dedicated to heroism, he introduces the term “banality of heroism”, derived, of course, from Arendt’s “banality of evil”. To me it really seems like Zimbardo had set from the get go a demonstrative goal of showing the symmetry between good and evil, inspired by Escher’s “Circle Limit IV”17 which appear twice in the book, at the beginning and at the very end, instead of letting the product of his investigation convince him.

Zimbardo’s take home message is that “heroes” are no different than any other “ordinary” person. He writes,

We may now entertain the notion that most people who become perpetrators of evil deeds are directly comparable to those who become perpetrators of heroic deeds, alike in being just ordinary, average people. The banality of evil shares much with the banality of heroism. Neither attribute is the direct consequence of unique dispositional tendencies; there are no special inner attributes of either pathology or goodness residing within the human psyche or the human genome.18

But he got mixed up. It is clear already in the preface where he writes,

By contrast, most others [other than the special and rare breed of heroes] we recognize as heroes are heroes of the moment, of the situation, who act decisively when the call to service is sounded.19

Rather, our banality of heroism conception maintains that doers of heroic deeds of the moment are not essentially different from those who comprise the base rate of the easily seduced.20

Suddenly an evil situation is both the cause of conformity-led wrong-doing AND of heroic-acts of resistence. So which one is it? Moreover, “when the call to service is sounded”? Who exactly is sounding this call? We are talking about situations where the group or society in which the individual is embedded is unanimously acting in a way that from a detached viewpoint might look unethical. If any call is sounded then it is not external but internal, meaning that it has to do with the individual and, if acted upon, is of course “not normal” for if it were then the group would not have acted unethically in the first place.

I agree that heroism, or, for that matter, evil, is not “residing in the genome”,21 but one certainly cannot say that it doesn’t reside in the “psyche”, and absolutely not say that it’s “in the situation” because it, very obviously, is “despite the situation”. Like Zimbardo I think that it, “heroism”, can be learned, that is, that a person’s life experience would affect whether they would act according to their moral compass (which by itself is a product of a person’s experience) and in defiance of society, or not, for example by having cultivated one set of values and not another.

But this point makes Zimbardo’s book inconcsistent. That last chapter includes a section, “A Ten-step Program to Resist Unwanted Influences”, which is meant to instruct the reader about how to resist unjust norms and systems. Whether his particular suggestions are effective or not is a separate issue; the important thing is that Zimbardo deems it possible to cultivate “heroism”, meaning that it is a quality that a person might or might not have, meaning that not everybody is the same in that respect (otherwise he wouldn’t need to include the section in his book), meaning that hereos (or potential hereos22) are not indistinguishable from non-heroes. Potentiality and reality are not the same. A company would not hire a person for an engineering position because she could be an engineer, but because she is one.

There’s a paper by Midlarsky et al23 that investigated the correlation between various psychometric traits (derived through self-reposted questionnairs) and having been, during the holocaust, a rescuers (of persecuted people), a bystander (non-rescuers who lived nearby) or an immigrant who left the country before the war. They found that they could set a discriminant function analysis classifier that correctly classified 93.1% of the sample when it had to distinquish between rescuers and non-rescuers (including immigrants). Moreover, looking at its confusion matrix, while rescuers were correctly classified 82.9% (63/76) of the time, only once (1.4%. 1/73) was a bystander misclassified as a rescuer. In other words, while the classifier sometimes mistook a rescuer for a bystander, it almost never mistook a bystander for a rescuer ––– suggesting, again, that there was something special about the rescuers. That is, assuming equal opportunity of “heroism” among them all, it seems possible that some “rescuer-types” did not have the opportunity to save others despite their character, while the “bystander-types” never saved lives even when having the opportunity to do so.

And here I want to return to the connection between “ordinary” and “orderly” alluded to before. The rescuers differed significantly from the other two groups on all measured metrisc, but I want to touch upon two of these, on which the rescuers scored higher. One is “risk taking” to which I’ll return to below, and the other is “autonomy”, measured with Kurtines’s autonomy scale. I feel like I should evoke dictionary definitions, but I think it should not be necessary. By virtue of being more autonomous, these people tended to align themselves unconditionaly with the order around them less than other, less autonomous, people. That is, what distinguishes those people who rescued the lives of people when the social order was persecuting them was precisely that they were less “orderly”. So, again, the bystandars, and, presumably, the active perpetrators, were not doing bad despite being ordinary, but “because” of it.

One issue with the study is that it was “retrospective”, interviewing and collecting metrics of people and associating it with events, things they had done, decades earleir. Did these psychometric metrics measure traits of the personality which caused these but not others to put themselves at risk in order to save Jews, or did this life experience change the way they view themselves or the world, thus affecting the metrics? I wonder if it makes a difference. In the former case we could have said assuredly that the character of people determined whether they had rescued or not. But what about the latter caee? We could think that the rescuer’s experience simply made them become aware of the kind of people they were, thus shifting their measured metrics.24 That is, even if they had not rescued (in the case that the holocaust didn’t happen, or they didn’t have an opportunity to save people’s lives) they still were potential rescuers22, but without the act they would not have become aware of that. But what if indeed the acts themselves transfomed not just their self-knowledge, but their characters per se? The answer to this question depends on the answer to another question, namely, whether the opportunity to rescue people was indeed “more available” than “taken advantage of”, or not. One possibility is that the opportunity to rescue was very rare but that most of the few people who had it used it to save people and had their personality transformed, in which case we could tell Zimardo, “yes, you are right. We are all heroes who just need the opportunity”. The other possibility is that the opportunity to rescue, whether rare or abundant, was used by only a small fraction of the people who had it, namely people with an extraordinary character. The latter seems more likely to me since “taking the opportunity” to rescue was very often a very active and involved activity ––– something that the rescuers indeed “took” rather than “received”.

Zimbardo puts his theory before the results of his experiment

Third, in his analysis and conclusions Zimbardo seems to turn a blind eye towards what was going on in his own experiment. While arguably by him the results of the experiment demonstrate his points, I think that even that is not the case.

Zimbardo talks about how ordinary people, his experimentees, were inserted into a bad place and were corrupted by it. This is a somewhat peculiar statement since prior to the beginning of the experiment, prior to the experimentees entering that basement, there was no “place” or “system” or “situation”, other than an abandoned university campus floor. The subjects were not introduced into a bad system but created it. Now, of course that creation was not “spontanious”, and, treating Zimbardo as an external force, we could say that Zimbardo created a bad system into which they were introduced. But a person (Zimbardo) addressing another person (any of the subjects) is hardly a “system”; only once all the subjects were in place at the begininng of the trial you could say that they constituted one. The point is that they gave rise to it together and all at once, rather than having been integrated into it.25 This is not merely a moot point: the “evil” of the system was created by the experiment subjects or a portion thereof, rather than existing prior to them; they brought it into the place, rather than the place putting it into them.

This is not just my theoretical conclusion. First, again, Zimbardo, from the website dedicated to the experiment:

Where had our “John Wayne” learned to become such a guard? How could he and others move so readily into that role? How could intelligent, mentally healthy, “ordinary” men become perpetrators of evil so quickly? These were questions we were forced to ask.26

I couldn’t find a contemporary account and the retrospectiveness of this statemet speaks somewhat to the possibility of inaccuracy, but I hope it could be fair to say that it could have been true. On a BBC documentary from 2002 Dave Eschleman, again, the “John Wayne” of the citation just above, said the following:

I arrived indepentendly at the conclusion that this experiment must have been put together to prove a point about prisons being a cruel and inhuman place, and therefore I would do my part, [laugther] you know, to to help those results come about. I was a confrontational and arrogant 18 year old at the time, and, you know, I said, somebody ought to stir things up a bit here.27

In light of this quote, read again the quote of Zimbardo above it. It is not clear from the quote when exactly he “arrived at the conclusion”, but he has been creative in his “abuse” from his very first shift, which was the second shift the prison had had. Since he alludes to the experimental facet of this whole arrangement, that is, it being a scientific endeavour, it is presumable that he had arrived at the conclusion before even coming to the prison, or immediately as he arrived. Either way, from within the experiment the situation was a state of make-belief, that is, “we are in a prison” and not “we are at an experiment”, so it is unlikely that anything in “the place” turned him to make that decision unless it was something that accentuated its experimental nature. In other words, he came into it with that decision in mind. How his behaviour affected his fellow prisoners is another thing, and in general Zimbardo is correct about bad norms developing and spreading. Nontheless, it is important to remember that the system is made up of the individuals constituting it and is not some entity that is external and above them, which is how Zimbardo treats it.

Alternatively one can take the “situation” to include not merely the make-belive prison but the entire phenomenon of the scientific experiment, so that Eschleman’s decision arose within it and not brought from without. This kind of treatment, incidentally, would include Zimbardo as a “perpetrator” not only in his function as a superintendent, but also as the experimenting psychology professor, and the “bad place” is not the prison per se but the psychological investigation. This makes it a little more complicated to comment about, and I’ll leave it at that for now. I will note however that it was within this scope that the experiment came to its premature ending: the woman who Zimbardo was dating at the time, and with whome he got married later, came to the place to pick him up to dinner and saw the experiment for the first time. She expressed great shock at what he was putting those men through and he terminated the experiment.

Whether Eschleman’s statement above accurately depicts his state of mind at the time of the experiment or not is less important than a bigger issue with Zimbardo’s analysis, and this would be my final point of criticism–––

Good and Evil is epiphenomenal to people’s interests and actions

Fourth, in his entire analysis, Zimbardo doesn’t allude whatsover to individuals’ interests and motivation. In his entire book, whenever interest comes up it’s either an experimenter’s interest in conducting an experiment, or individuals interest in belonging to a group. The latter is a real and important interest of people, but people’s desire to be part of a group often stems from interests other than the “wish to belong”, and I think that a wish to belong can often, if partially, be attributed to other more basic interests. In Zimbardo’s analysis “good” and “evil” are almost like primary movers to whom particular human behaviour is epiphenomenal. The evil system is deterministic, compelling behaviour, and there is but one axis in which one could behave, either conforming to the system or resisting it. To me this seems utterly wrong, even opposite of what is the case: people have interests, they are situated within an environment of which they have a limited perception and understanding, and within their freedom and potential to act they pursue their interests, and one can describe this or another act as “good” or “bad”. As for systems qua cognitive constructs/ objects, they conceptually simplify the environment and loosely dictate rules of engagement, mutual and otherwise, within which individuals behave, again, according to their interests.28 In other words, strictly speaking the system does not define how the actors within it are to behave, but what effects actions taken within it would have. Even when some norms are very strongly ingrained, people do not mistake them for physical laws but are aware that unlike the law that compells the stone to fall down to earth, it is within reality’s possibility that the law “thou shalt not kill”, for example, will be broken. When rules of conduct are explicitely encodes, often the code also encodes what is to happen when the rules are broken, such that it is not only “thou shalt not kill” but “if one kills, one will face such and such of a puhishment”.

The only time Zimbardo talks about interest ––– in the form of desire ––– is when he brings up the idea of Appolonian and Dionysian natures. The following is a little redundant, but I want to present it for the sake of completion.

Let’s assume that the “good” side of people is the rationality, order, coherence, and wisdom of Apollo, while the “bad” side is the chaos, disorganization, irrationality, and libidinous core of Dionysus. The Apollonian central trait is constraint and the inhibition of desire; it is pitted against the Dionysian trait of uninhibited release and lust. People can become evil when they are enmeshed in situations where the cognitive controls that usually guide their behavior in socially desirable and personally acceptable ways are blocked, suspended, or distorted. The suspension of cognitive control has multiple consequences, among them the suspension of: conscience, self-awareness, sense of personal responsibility, obligation, commitment, liability, morality, guilt, shame, fear, and analysis of one’s actions in cost-benefit calculations.29

I would argue the exact opposite. It is exactly when people conform to an “evil system” despite holding it to be immoral that they are being “orderly”, that they are being constrained. It is in this situation that their sense of fear, obligation and commitment is hightened, not suspended. It is no coincidence that otrocities committed by societies happen in the context of an authoritarian regime, that is, one that holds its power through coercive violence more than through persuasion. Othrewise the subjects would not have been subdued and would not commit the vile acts. It is the case that in such situations they lose their autonomy, but they do not lose it to an internal release of lust and desire, but to an external controlling power:

Order is good/evil agnostic

Power is what keeps the realm, the potential space of appearance between acting and speaking men, in existence. The word itself, its Greek equivalent dynamis, like the Latin potentia with its various modern dervatives or the German Macht (which derives from mögen and möglich, not from machen), indicates its “potential” character. Power is always, as we would say, a power potential and not an unchangeable, measurable, and reliable entity like force or strength. While strength is the natural quality of an individual seen in isolation, power springs up between men when they act together and vanishes the moment they disperse. Because of this peculiarity, which power shares with all potentialities that can only be actualized but never fully materialized, power is to an astonishing degree independent of material factors, either of numbers or means. A comparatively small but well-organized group of men can rule almost indefinitely over large and populous empires, and it is not infrequent in history that small and poor countries get the better of great and rich nations.30

It is certainly true that there are wrong doers who commit vile acts at moments of loss of self-constraint to e.g. a momentary overwhelming ire. The reason Zimbardo confounds these people and their actions with the doers of evil out of conformity is beacuse, again, he takes Evil to be some sort of absolute, perhaps one could say a metaphysical one.

Morality is a social matter. One can hardly think or discuss the morality of a person in seclusion from others. Morality refers to the adherence to some sort of code.

Moral judgements are not absolute. They always refer to a particular ––– not universal or absolute ––– code, and are restricted by undersanding. When Alice judges morally an action of Bob, her judgment is restricted by (1) what she knows of the context, and (2) by the different frames of reference her mind lends her by which to conceptualize the action that.31 Second, and more importantly, her judgement of Bob’s action is based on her own particular “moral compass” which derives from her world-view/ideology.

The difference between the control-losing person who steals, assaults or kills and the person who does those things in alignment to “bad norms” is that the former, whether he justifies his actions to himself or not, acted generally against the moral compass he holds and shares to a greater or lesser extent with the individuals of the group he belongs to, while the latter does them in accordance to the compass. The most obvious example is that of a war situation. A soldier killing an enemy did not “murder” but did a virtuous act, in accordance to a patriotic world-view and within the strife of his nation against the enemy nation; a person killing a fellow citizen has indeed “murdered” for he broke a code.

Of course, the state of war and the geographical separation of differentiably treated people is but one example. The holocaust is an easy example of a time where different people within a single society were treated differently to an extent where it was permissable even to kill the members of the group that was not holding power. Another is the diffrential treatment of women in different societies in different times.

The “condemnation” of past cultures and their ethics is of course not a real judgement, but an analysis, a thought-experiment, being conducted by the present culture in order to define its own ethics; the past is past. A little bit like the way that the certain “standard” accents, be it BBC English, “general American” or High German, are regarded as being “accent-less” so often when judging societies of the past or simply other contemporary societies there’s a sense in which one feels like one’s own is a universally good moral compass, while that of others is deficient, either not progressive enough or too desolute. To be just a little provocative, let me bring to the fore these: we are indignant thinking about how African people were brought to America to serve as slaves, toil at the fields, owe nothing and be treated as less than human; or be cynical when thinking about the “Athenian democracy” and refer to the fact that slaves constituted the majority of Athens, and that only the land owners had the right to vote. Nonetheless, under our capitalist ideology, it seems fair and just to many that some people would toil and owe little just because they or their parents didn’t ship books sold online from their garage or create an online student directory from their dorm room, nor do people seem particularly outraged by the mechanism of lobbying and its gift-giving, where individuals and organizations with considerable wealth directly influence law-making through legally-acceptable bribery. That the evaluation of other societies is done with one’s own compass and not some “universal ethics” (which really cannot exist) can be also hinted at by this one example that Žižek brings up in a talk:

You know our media are now are full of that […] [Jamal Khashoggi], the Saudi Arabian guy, killed in […] you know what I find a true scandal in it? Not the fact that ––– of course it’s terrifying what the Saudi Arabians did ––– but, we get so excited about this one guy who was one of us, privilaged, living in the United States, part of the royal family, you get in the media. While Saudia Arabia is systematically destroying an entire country, Yemen, now. Bombing children and so on ––oh! that’s, –you don’t talk about that. That’s the true scandal of it. It’s a totally displaced sympathy and so on. It’s a nightmare. It embodies, again, everything that is false. 32

In the moral comparison we take Saudia Arabia to stand for an autonomous country like our own, and what terrifies us ––– and perhaps all the more so the journalists who are behind the media that covers the incidents ––– is the act of murdering a journalist, a civilian, in a process of silencing dissent. The subjugation of other countries that cannot defend themselves is “ok” if only through tacit acceptance. The so called “Western” countries themselves benefit from such exploitations, whether it is the intervention of the USA in the politics of various countries in America, or the state of chaos and civil war in the Congo or other “conflict zones” which makes cheaper the extraction via smuggling of Coltan and other minerals which power our smartphones and electric cars, a trade that both benefits from the state of violence and also finances it.

In other words, what is considered “right” and “wrong” is not handed from above33 but is defined by society, and while one can judge the norms of society both from within and from without, this judgement is merely made by a different set of mores. Acting as a group the individuals make compromises for the benefit of power stemming from a coordinated action, the same way that the cells in a multicellular organisms in a sense conform to a standard by restircting their freedom in order to form, together, the more powerful creature. Whether that creature fares better or worse than other single cell organisms in the environment is another question. Being “ordinary” or “orderly” simply means adhering to the order dictated by society, itself a superorganism, and does not imply how “good” or “bad” one’s behaviour is according to an arbitrary moral standard.

Cruelty to keep the rank and file of the aggressors

Why did no other guard stop the cruel guard?

The reason that I behave nicely with people is partially out of empathy,34 as well as out of habit, but here I want to discuss another factor which I think is important. This other factor ––– which is not at all separated from the first, empathy ––– comes into play whenever any calculation of action is going on, namely, when there’s a large discrepancy in the outcomes of different prospective actions as well as the leisure for the act of consideration to take place. In such instances I often go for “nice” because inherent to my process of thinking is the belief in every person’s ability and potential will to hurt me in one way or another. This, I think, usually comes in the form of imagining a certain particular way in which they could hurt me back, regardless of whether it is congruent with their personality and habits or not. I have a rather anxious disposition and the idea of drawing the enmity of other people towards me is repulsive, for a lack of a better word; it is the opposite of attractive, the opposite of appealing. Generally speaking –– not without exception –– I try to avoid that. I imagine that such a cynical look would be objected once it is pointed not at myself but at others, but I think I’m not an anomaly in this. I imagine that the calculated good behaviour of many people is motivated likewise.35 A corollary is that people who act less nicely than others are less afraid from “second parties”.

This point of view can be applied to analyze the happenings of the prison experiment. The aggressive guard is not afraid of the prisoners, while the other, good, guards, in some way, are. First, as for the aggressive guard, Eschleman, I think it is also evident from his words at the debriefing. It could be that his “courage” was dispositional, but it could also be that it was mostly drawn from the way he had construed the situation he was in. He said that he was running his own “little experiments”; the whole thing was a large “make believe”, they were not “really” prisoners or guards. It was a big “game”, and like in chess where I capture your queen not out of spite, so anything that happens within the framework of the prison experiment can be regarded as an action taken with correspondence to the established “rules”. This is in congreunce with Zimbardo’s idea of deindividuation, the idea that anonymity put upon a person facilitates perpetration but I want to go a little farther (and a little alternatively) in explanation, saying that this functions not through some abstact sense of not having a responsibility, but of feeling safer against retaliation, either due to anonymity (identity is intractable and therefore it is impossible to make a personal retaliation) or because the “real actor” is perceived to be someone else, whether a person or an organization, and therefore the perpetrator expects retaliation to go against these rather then against himself. In the prison experience the perceived responsible actor would be Zimabrdo. The sense of safety from retaliation could all the more so derive from the fact that not just the guards but also the prisoners volunteered themselves, that is, entered the circumstances willingly, so in a sense Eschleman only acted in accoradnce with an agreed upon arrangement.

As for the good guards, I imagine, they were afraid. First of all although perhaps less importantly, from the prisoners. This is what made them “good”. During the experiment they had the upper hand but that experiment had a not very long expiration date –– two weeks after it had begun –– and all the participants were students at Stanford, and therefore to some extent part of the same society. More immediately however, the easiness of handling the prison relied on the cooperation of the prisoners. The guards were at least symbolically armed with batons but nonetheless the prisoners were men and therefore had the potential of using violence. And without exerting direct interpersonal violence the guards had the potential of making things difficult for the guards.

More importantly, however, is that the good guards were afraid, and much more so, from the aggressive guard. I believe that the same consideration that makes them avoid “interfering” with others and thereby hurting them, is the same kind of consideration that makes them avoid interfering with someone whose actions are regarded to be bad. They did not come to protect the prisoners from the aggressive guard because they were more afraid of the guard than from the prisoners. First, the guards had significantly more power than the prisoners; the prisoners were weak in relation to the good guards, while the bad guard was “one of them” and therefore capable of hurting them just like anybody can hurt his peers. Further, the guard was exhibiting aggressive and even sadistic behaviour, and even though it is not directed at the other guards, it is threatening. This display of aggression makes the potential of that guard’s retaliation seem more likely and perhaps more grave.

In other words, “giving way”/”non-interference” is, like cooperativity above, “good/bad” agnostic; generally speaking it can be taken as a positive good trait, taking into consideration others in one’s action in order to minimize interference. When those others are “doing bad” then this non-interference can be regarded as a negative “bystanding”, allowing perpetrators to do bad with little hinderance. Both patterns of behavoiur stem from the same motivation, seeking to minimize conflict between one’s self and others.

This analysis sheds light, I think, on some of the things that occured during the Rwandan genocide and other such horrors. Zimbardo’s book describes in detail the abhorrences occuring during the genocide, including violent slaughtering, also done by former neighbors and friends, violent rapes and sexual torture, and such coercions as making a man rape his mother in front of his father while his other siblings are restraining her. Not only do these actions seem terrible beyond words, they seem arbitrary, evil with no reason. Whatever political goals the Hutu were trying to achieve through the systematic annihilation of the Tutsis, the violence seems like an excess, not only not facilitating the political goals but actually hindering them by diverting time and energy to actions that are not expedient. But I claim that it was not arbitrary but an integral part in the dynamic of keeping the whole operation running. I’ll add, too, that this excessive violence was not occuring because the Hutu were sadistic people, but precisely because they weren’t.

Before continuing to my own idea, I’ll just mention one other pruposed function of wartime sexual violence:

Military strategists may regard this activity as a waste of valuable resources and manpower. Moreover, troops would be potentially exposing themselves to venereal diseases while commanders run the risk of losing control of their men, making their units combat ineffective. However, the Hutu leaders and sponsoring government understood the power of the message. To them, it was not counter-productive to kill women immediately after they were raped, so long as a select few lived to tell the story; women like Rose. Therefore, rape warfare exemplifies intimidation in its most malevolent form.36

The idea –– which is scatred in the article cited above –– is that this excess violence is used to “strategically target the psychological well-being and social cohesion of civilian populations as well as the morale of enemy units”, and is “reducing the cohesion of family units and the community as a whole”. This doesn’t seem right to me.

Intidimation, as a tool, is used to either minimize energy expenditure when subjugating another, or as the subjugation itself. That is, it explicates a potential imminent punishment that would be delivered if the second party doesn’t comply. It forces cooperation with minimal exertion of energy, either through the use of words, or with restrained violence that promises the potential of greater violecn upon non-compliance.

I don’t think that the excessive Rwandan genocide violence fits the profile of “intimidation” because, to begin with, the Hutu did not seek cooperation from the Tutsis. Had they merely tried to conquer them, subjugate them sociopolitically, then this violence could be used to assert control. However, their goal was to annihilate them: if the Tutsis could cooperate in any way it would only be by lending themselves calmly, sheepishly, to the killing, which is supposedly the very opposite of what you get by stirring up panic.

The advancing of the horror stories ahead of the Hutu militias must have been to the detriment of their project, as it could have united the Tutsis, making them more prepared for the former’s arrival and therefore showing greater resistance.37 Because of this I don’t think that the excessive violence was used to intimidate the victims. Rather, it was used to intimidate the aggressors themselves; as far as these atrocities were a “message”, it didn’t communicate with the victims, but was reflexive, a communication from the group to all of its members.

The sadistic behaviour is applied on the other, but the function of its excess is to serve as determent to the individuals constituting the aggressors. Had the decimation been “professional”, the participants, the Hutus in the Rwandan genocide, for example, would have known that they are safe to make objections since they are not Tutsis and therefore are not qualified to be subjected to that violence. However, when the violence is arbitrary in one aspect, for example in its execution, then it suggests that it could also be arbitrary in other aspects, such as its targeting. Moreover, the arbitrary violence makes it look like all the others are relentless merciless people, and being fearful one doesn’t want to draw their enmity to oneself by confronting their actions in any way. That most of the others are acting through the same motivation (fear for themselves rather than hatred for the other) is inconsequential since one is not privy to the thoughts of others. On the other hand, the coalition of the aggressors and their complete power over the victims exemplified via the excess, creates a sense of protection from the latter; a “marginal triumph” could give a sense that the tables could turn, but an overwhilming one can give a sense of invincibility and therefore a sense of protection amidst the aggressors ––– as long as one belongs to them.38 Again: the excess of the brutality is inflicted on the victims but is “directed” at the perpetrators, holding them united in their action.

I take a look at myself and I am concerned. This same cowardice that makes me “behave well” in general is that which makes me behave ineffectually in the presence of injustice. I was once walking in the street with a friend quite late at night when on the other side was a scene. A guy was shouting at a woman. None of us spoke German and we couldn’t tell what he was saying. The woman seemed very much distressed. My friend stopped us, asking if we should do anything. My response was if not literally then effectively a shrug; to me it was the argument of other people, and even if it was realized in that heated form it was still their business to make their resolution. I did have pity towards her but I suppose I was also afraid of the man. Perhaps their fight was their business but it occurred nonetheless in the public sphere and was therefore open to public scrutiny.

My friend turned to the woman and asked her, in English, if she was ok. The guy shouted at my friend something along the lines of “mind your own business” but she ignored him. The woman made some sort of “it’s ok” gesture and we left; at the end we also didn’t have the lingual means to communicate very well. Perhaps the woman was afraid from the guy such that it was better to dismiss external help, but if the situation were extreme then we –– that is, my friend –– at least offered her the opportunity to take on the support of a third party.

I think I’m far from being a pushover, but in situations like this I don’t behave the way I wish I would. I’m meek. I think I can think myself into acting “correctly”, but it doesn’t apply to these sudden events. Maybe –– a big MAYBE –– if it was a repetitive event. I think long and therefore act slowly. I hope that this recognition of mine could be a potential source of deliverance from bystanding.

Jerkiness: one sign of courage?

Is this, perhaps, why some women are “attracted to jerks”? I sniffed around the internet and saw that people say that jerks are confident, and that this is what attractive about them. To me, however, it begs the question, “what is confidence”? Or at least I state it rhetorically, because I had looked for answers alternative to my own but found only opinions that agreeed with mine, though stated in different words.

I have for much of my life considered myself to have high self-esteem but low self-confidence. Though I knew what kind of experiences I was basing this judgement on, I didn’t know from what traits of mine these things had risen. That I was very anxious I knew, but now I’ll add that I’m quite the coward as well (I have counter second thoughts about it now, but I’ll leave it as that).

There is this oft given advice for guys who are too bashful to make a move at someone attractive to them that “they have nothing to lose”: the worst that could happen is that they would get rejected. While this is true, I had always found this advice to be somewhat unhelpful, and one day I realized that there was an aspect that had been overlooked there. This is true for me, and I imagine that it is also so for others: I felt that the reason I was “against”, indeed, “afraid”, to make a move on somebody was that I didn’t want to put that other person in the position where they want to reject me, but feel bad about it.

This is not unlike when you have a friend whom you don’t want to bid for an extraordinary favour and have them either acquiesce begrudgingly39 or turn you down without a sound excuse, either way besmirching the reciprocal relationship.

I was not afraid of being rejected, but was considerate of the other person, as it were, unwilling to put them at the uncomfortable position.

In those cases there was no retribution that I imagined and was concerned about, but perhaps here was an overgeneralization that “discomforting others is bad”. I think part of it all is also an instinct that stipulates the reception of signs of interest (e.g. significant eye contact) from the woman before action, but from experience I know that even when receiving these signs from an attractive person I had been anxious to make an approach. It was then all the worse since these signs felt like a demand of action, in a way, such that a failure to react amiably to them would be to signal a rejection from my part ––– so that both approaching and not-approaching seemed like unfavourable moves, and the only alternative was to completely vanish from the scene. Clearly something is not very consistent in my behaviour and thinking. Perhaps it’s bad habits. Need to do some thinking and reevaluation.

Anyhow, jerks have confidence, that is, courage, which of course is not to say that confident or courageous people are necessarily jerks; they “dare” act for the benefit of their interests with some disregard to what other people might do or think in reaction. The jerkiness itself might be a bad quality, but it’s a symptom of, among other things, confidence, a good quality. And this is that which is attractive, and I suppose this is also true when the genders are switched, or equated. I’d even stipulate that people have an inherent attraction to that trait in partners, so that even if jerkiness is the most salient or even exclusive realization of that confidence, one would be attracted to them; this jerkiness might not benefit their partners, but it will their mutual babies in the form of inherited courage/confidence, and perhaps in the form of resources (available to the children? And to the partner too?) gained from exercising confidence, i.e. not relenting to others. And, even if it only manifests in jerkiness in the kids, that could alone be an advantage at an environment where jerkiness is remunerated, regardless of what god, who has little power of enforcement, thinks about it.

Not by dread alone

I do not think that the only thing that leads people to “be good” is fear of retribution. For example, just as a person might have such inherent appetites that make sadistic or domineering actions be satisfying, so another person might find pleasure in helping a person in need. I do think, however, that by and large what holds together an orderly society is exactly that fear, whether you have something like a centralized authority and police ––– where this order is less bloody ––– or not. But this is only one half of the story. One could also say that what holds society together are conditions that render cooperativity profitable. These conditions can be both static, such as a certain level and distribution of resources, a climate, and so on, or dynamic, such as a certain prevailing culture of interaction between people and groups. To take these together, one could say that what holds orderly society together is the firm conviction that cooperation is advantageous over conflict.

Explicitely stated, it sounds somewhat off, the fact that what keeps the order is the fear of retribution. Where I currently live, in Berlin, generally a very orderly city, it feels like people are just “spontaniously” orderly, that they are nice and law abiding simply because it is “good”. But this is deceptive, and I think that in a way the very seeming absence of law enforcement activity or presence –– there’s no cop on every crossroad, or anywhere at all but sensitive locations –– is demonstrative of its power. Everyone is aware that given a transgression the police can be called upon, and while the great majority probably didn’t have an experience that would back it up, they believe that the response would be prompt. There’s a sense of safety backed by the power of the law.

In addition, the absense of police presence on the street adds to the sense that enforcement is not arbitrary. Even without abuse by bored policepeople, their presence could suggest that enforcement would depend on their perception –– such that the power of the police is diminished behind street corners that are beyond thier sight –– as well on the particular officer (and his mood) who is stationed at the crossroad, as opposed to the abstract and pure power of the police that is absent physically but can be at any moment summoned. Arbitrariness, adding uncertainty to enforcement, disturbs the optimal inequation that holds cooperativity advantegeous over conflict since it makes both the punishment for transgression as well as the freedom from police harrasment during cooperativity less certain, making cooperativity a less attractive option.

On the same note but as an aside I’ll add that forgiveness is not merely a “gift” to the forgiven; it is the termination of hostilities. Even if a tat justifies a tit, it continues a state of hostility. And just as a war is a very taxing activity, so is an interpersonal conflict, perhaps with even less potential for bounty. Asking forgiveness in a sense nullifies the need for retribution. If titting for tat can serve as deterrence from future grievances, proving to the original offender that “crime doesn’t pay”, then asking forgiveness is to admit that “the lesson was learned” without the lesson. It is to say, “I respect you as a person who is capable of hurting me back”, implying that “I shall not do X again”. That one can maliciously take advantage of being forgiven and therefore being exculpated is another matter; one can dishonestly ask for forgiveness just as one can dishonestly use words in many other ways.

Heroic goodness out of Courageousness

Cowardice facilitates ordinary orderly cooperative goodness. To refer to the inequation mentioned just above, cowardice makes more salient and important the likelihood of retributive punishment, making the cooperative option more likely to be taken. This doesn’t mean that all courageous people are criminal, though I do think that all else being equal they are more likely to be so. On the other hand, it doesn’t mean that all criminals are courageous. Some might be driven to that out of necessity, such as people who have nothing to eat and nobody to lend a hand to, and they turn to stealing, for example, to merely survive. But then you also have some who have something to lose, can get by by being law abiding but who potentially could gain something by breaking the law. Here ccourage lends itself: it is the courageous person who goes to rob a bank, not a cowardly one.

Likewise, at times where society turns to commit atrocities upon a population of human beings, it is the courageous people who go against the seeming consensus by helping the oppressed instead of passively standing by or even joining the perpetrators. Please notice that it is not an “additional emergent property” of courageous people, but one and the same phenomenon differentiated by a value system. After all, those goody two shoes are criminals, whether they are breaking the law of a centralized civil government such as that of Nazi Germany, by hiding Jews, or the law of violent militias and militarymen during the Rwandan Civil War, by refusing to kill Tutsi. What these law breakers seek to gain is different from other “more common” premeditated law breakers, though this differentiation, in some way, is also a value judgement.40 To put it simplistically, they seek to appease their conscience.

In the study described in the paper by Midlarsky et at mentiond above, the investigators found that rescuers were high on both of the metrics of “empathy” and “risk taking”. This is if not expected than at least reasonable, since all the rescures had put themselves at grave risk when enacting the eponymous act, and all presumed to have been motivated by empathy towards the persecuted. A curious thing is that those two metrics were significantly correlated with each other, that is, people in their sample tended to be higher on one metric when they were high on the other, and vice versa. To me this is unxpected since nothing in my experience suggests to me that the two, as human traits, might be correlated.

The idea of people who are capable of taking great risks while not being particularly empathetic people,

or of empathetic people who are not courageous, doesn’t seem strange at all. On the contrary, I’d say that if anything I would have expected the two to be anticorrelated, but this is probably due thinking about very specific manifestations of “risk taking” which are but a small portion of “risky” activities.

One possibility is that this result is a product of a sampling bias. In the study the experimenters didn’t just pool a sample of people who had survived the holocaust41 and then separated them into groups of rescuers and bystanders according to their conduct at the time. Rather, they sought out rescuers who had not been interviewed as such, and then sought out bystandars who lived in proximity during the concerned period. The number of holocaust rescuers was in the tens of thousands, but that number is miniscule compared to the hundreds of millions of people situated there where the holocaust took place. Assuming that high risk taking and high empathy are rare in the population, then the selective sample that picks out those whose activity, rescuring of Jews, was a phenomenon emergent –– ostensibely –– from these traits, would greatly skew their distribution. If the two are present at high values among the rescuers, but are uncorrelated in the bystanders, then, as the two groups are comparable in size, you’d get a high correlation.42

I think looking at the summary statistics (table 2) is suggestive of the above. The mean of the metrics of Risk Taking and Empahy of the bystanders was 1.477 and 1.274 standard deviations below that of the rescuers, respectively. If we assume that these are independent (which is what I want to show? ehh..) and that each metric score has a normal distribution,43 then only 7% and 10% of the bystanders have a Risk Taking and Empathy score, respectively, as high as the mean score of the rescuers. That is, only 0.7% of them have both scores at least as high as the rescures’ mean, in comparison to 25% of the rescuers ––– a rate that is 35 times lower (the immigrants’ scores were closer to the rescuers’ in comparison to the bystanders, but overall their were much closer to the bystanders’ than to the rescuers’). In other words, assuming normal distributions, the statistics of the rescures’ are extreme enough that including them at the biased-sampling-rate of 40% (their portion of the study subcjets pool) up from their natural occurance rate of less than 1% could lead to the emergence of spurious statistics such as correlations between variables that are otheriwse not correlated, so I’d say that I’d go with the null-hypothesis that these are indeed independent. This could have been easily checked by checking for correlations within groups instead of across.44

How to make people be good

Crime Enforcement

No society can afford not to defend itself against deviance, not to attempt to change those who oppose its rules and structure. In spite of thousands of volumes on the subject of penology, the philosophy of justice has never been, and perhaps never will be, able to lift the function of punishment out of the paradoxical contamination of retaliation, deterrence, and reform. Of these three functions the last, reform, is unfortunately at the same time the most paradoxical as well as the most humane. While we are clearly not competent to deal with the extremely intricate problems of a humane administration of criminal justice, the impasses produced by the attempted changes of an offender’s mind and of his behavior can nevertheless be appreciated also by the layman. Whether the setting is a maximum-security prison or merely Juvenile Hall, the paradox is the same: the degree to which the offender has supposedly been reformed by these institutions is judged on the basis of his saying and doing the “right” things because he has been reformed, and not because he has merely learned to speak the “right” language and to go through the “right” motions. Reform, when seen as something different from compliance, inevitably becomes self-reflexive—it is then supposed to be both its own cause and its own effect. This game is won by the good “actors”; the only losers are those inmates who refuse to be reformed because they are too “honest” or too angry to play the game, or those who allow it to be apparent that they are playing the game only because they want to get out, and are therefore not acting spontaneously. Humaneness thus creates its own hypocrises, which leads to the melancholy conclusion that in this specific sense it seems preferable to establish a price to be paid for an offense, i.e., a punishment, but to leave the offender‟s mind alone and thereby to avoid the troublesome consequences of mind-control paradoxes.45

Wikipedia lists several objectives of criminal law, which are easily conjurable by anyone meditating on the subject for a few minutes, had they never done it before. As far as penal emprisonment goes, it serves to 1. deter, 2. serve as retribution, 3. remove the offenders from society, and 4. rehabilitate. As described in the quote above, rehabilitation, presumably the noblest of the four, is also the most paradoxical. That is, when this objective is integrated into the punishment and manifested in the form of paroles granted for “good behaviour”, i.e. successful rehabilitation. The paradox arises from the distinction made between “play-acting good” in order to receive parole, and “really” becoming good (via introspection, contrition and so on). If you just “act good”, “fake it”, ostensibely you should not be paroled; on the other hand, prisoners who “really are becoming good” are facing the issue of knowing that their good behaviour could have had the ulterior motive of shortening their prison time and of therefore needing to downplay its significance, as if the reward of parole should not alter prisoners’ behaviour but only be epiphenomenal, as it were.46

A way out, I believe, is to stop being concerned about the “moral character” of the prisoners, and instead concentrate on their adaptability to society at large, that is, on how well they could cooperate (i.e. be law abiding citizens) once they are free. This is certainly not a new idea, but I think often it is thought about too abstractly. The legal system, that is, the laws and their enforcement (including the correction facilities employed) should be designed thus that “crime doesn’t pay”, that is, that transgressions are ultimately to the detriment of the transgressors, and obviouisly so. Since cooperativity is a skill, the educational system takes a part, and the “correctional” in “correctional facilities” stands also for the ad hoc corrections made to the educational system that failed topically. The state, therefore, should erect institutions that: 1. give the impression that transgressions are detrimental, and 2. facilitate cooperation between people. These are simply two sides of one effect, namely, making cooperation seem more adventageous than non-cooperation in every circumstance.

One issue with good correction is that it might be deemed too generous by the population at large. For example, if while they are incarcerated prisoners receive professional training and even some sort of support in securing a job upon their release, then in a sense not only do they receive these benefits for free, but even as a “reward” for their misconduct, which can be perceived as unfair especially by disadvantaged but law abiding citizens. This could be mitigated if all citizens had access to such trainings (which would likely drop crime rates), but of course the funding of such institutions would have to compete with other expenditures of the government. That being said, it, the training of all unemployed citizens, seems to be a net benefit to society, assumig that the resources input into turning an unemployed resident into an employed would quickly shrink by the resources rendered by the latter after they start working. This notwithstanding, present resources often must be allocated towards the preservation of the state against existential risks, real or potential (such as threats from other countries), so they may not be always available.

What is goodness?

Selfishness and Altruism

It seems to me that often, to some extent, “being altruistic” is equated with “being good”. Certainly, “being selfish” goes well with “not being good”. However, I have developed an issue with the concept of “altruism” after I had read The Selfish Gene, and now I also find it being stated at the abstract of the Wikipedia page of the term:

Much debate exists as to whether “true” altruism is possible in human psychology. The theory of psychological egoism suggests that no act of sharing, helping or sacrificing can be described as truly altruistic, as the actor may receive an intrinsic reward in the form of personal gratification. The validity of this argument depends on whether intrinsic rewards qualify as “benefits”. The actor also may not be expecting a reward.47

It seemed to me that altruism, properly speaking, was impossible. When a person does something for the sake of another, it is either because they hope that it will grant them a possible future benefit, or because they are simply glad to do it. In the former case we say that the action is not altruistic since it is motivated by an interest of the self. However, in the latter case the doer has some sort of intrinsic drive that leads them to do that “act of kindness”. Its non-fulfilment causes pain (“I feel bad for just ignoring them”) and/or the fulfilment causes pleasure. Therefore ––– I thought –––– the seemingly altruistic deed is really just a selfish act that takes aim at the perceived well being of certain other people; if there was no pleasure inherent to the act’s execution, it would not have been done.

(I had sensed that a big problem of this model was that it didn’t explain anything, though I couldn’t tell exactly how so. Wikipedia cites Joseph Butler who first(?) pointed to the circularity of the argument, which clarified that feeling of mine. Essentially the above postulates that “people only perform acts that give them personal enjoyment” and concludes that “people only perform acts that give them personal enjoyment”.)

Later I thought I had “solved this issue” by putting the boundary between humans and their environment, treating humans as black boxes, and judging them solely by their behaviour and its outcome and not by their motivation. In this care we don’t care about the innerworkings of the actor, only of the interests of other people. I saw it better than my “every-act is selfish” (EIS) model since 1. There really do seem to be acts that are “altruistic”, and this model allows for their existence, and 2. It avoids some inconsistencies within the other model. I have held this model in my mind for many years as a sound model, but as I came to write it down now and explain the incongruities of the EIS model, I came to see the incongruities of the “black box agents” (BBA) model and was led to form my current “definition” of altruism:

The EIS model failed, I thought, due to its lack of the notion of “self”; a model, such as the BBA, that assumes that there are human agents with interests and examines the benefits of actions according to whose interests they are fulfilling allows for some meaningful distinctions. In the EIS model, for example, an act that is done by a person which causes her pain in the presence but benefit in the future is regarded as selfish. However, what if a person does despite herself something that brings her some pleasure at the presence but great pain in the future? Was that selfish, or anti-selfish? Certainly, one cannot ignore intention here: the former is selfish because it was done with the intension of gaining future interest, while the latter is selfish because it was done with the intention of gaining immediate benefit. Similarly are “altruistic acts” which are selfish because they are done with the intention of gaining the pleasure of feeling good about having done something good.

In the alternative BBA model we can say that the former action was “prudent” and the latter was “impulsive”, where we differentiate between the “present self” and “future self”, while the “altruistic” act is simply “altruistic” as it is done for the sake of a non-self. This is not a distinction that the EIS model can make. Is doing something for another without real expectations for future reciprocity of any kind is “impulsive”, or “prudent”? Well, perhaps they are “impulsive” indeed: if I give my food while hungry to another person who seems to be even hungrier than me it is perhaps because guilt is eating me from the inside. People who had done heroic feats such as rushing into a burning building in order to save somebody always (as far as I can tell) say when interviewed that they acted without thinking, that is, impulsively. I can imagine people embarking on endeavours that are meant to help strangers in some future; is that done impulsively, or is that some sort of prudence that takes a larger scope –– the community and not just the self ––– into consideration? I cannot say. Either way, the EIS model really is useless in clarifying anything. I think it’s not disputed that people are in the most reductive sense autonomous agents; what the EIS does is “rephrasing” the notion of autonomy in other terms ––– in terms of purpose instead of cause, if you will ––– and then point and say “aha! All are selfish” when really our experience is that “selfish” and “altruistic” (or at least “not selfish”) are meaningful distinctions as far as people and their behaviours go.